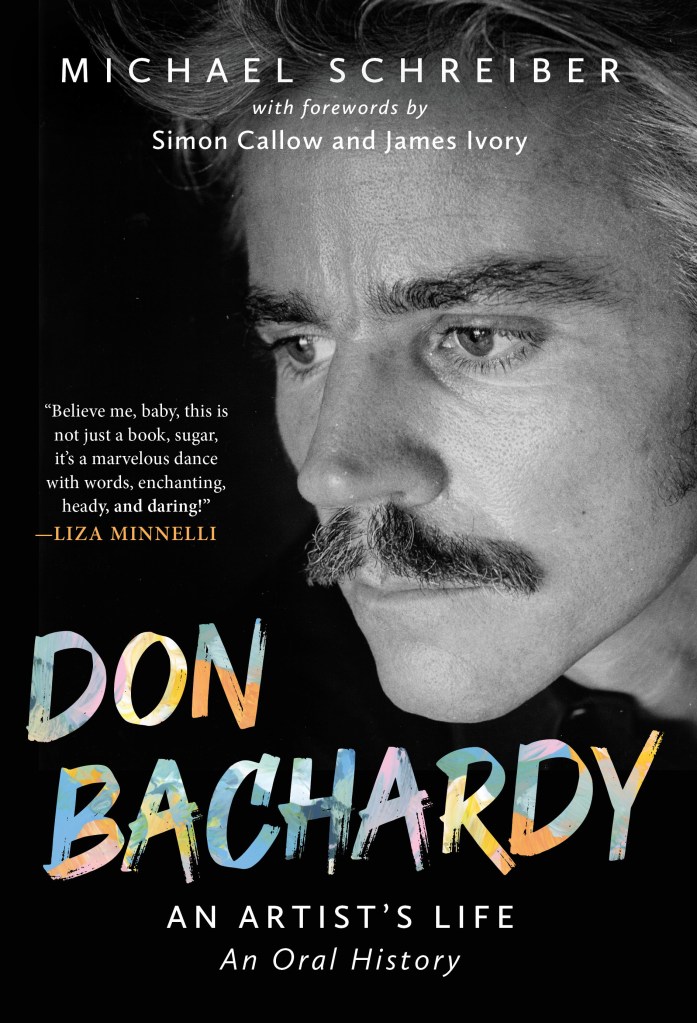

When Liza Minnelli blurts out, “Believe me, baby, this is not just a book, sugar — it’s a marvelous dance with words, enchanting, heady, and daring!” …you pay attention.

And that’s exactly what writer and oral historian Michael Schreiber delivers in Don Bachardy: An Artist’s Life, a sweeping, intimate, decades-in-the-making oral biography of one of the most important queer artists of the 20th century. It arrives buoyed by a dazzling constellation of contributors — James Ivory, Simon Callow, Tom Ford, Joel Grey, Sir Ian McKellen, Edmund White, Michael York, Robert Wagner — a lineup that reads as much like queer cultural history as it does a table of contents.

Schreiber, known to many queer cinema and photography lovers for his work on George Platt Lynes and as curator of artist Bernard Perlin’s estate, has spent years excavating and preserving the intertwined histories of queer creatives who made art—and love—fearlessly long before it was safe to do so. If you appreciated the documentary Hidden Master: The Legacy of George Platt Lynes, you’ve already been touched by Schreiber’s impact.

Now, following the record-shattering £33 million sale of David Hockney’s Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy—painted 57 years ago and still electrifying the world—there has never been a better moment to revisit the love story, artistry, and activist legacy of this iconic couple.

In this exclusive interview with YASS Magazine, Schreiber invites us into the room—literally—where he spent nearly a decade recording Don’s life, his memories, and his still-living love for Christopher Isherwood.

Hockney’s Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy just made history at auction, selling for a staggering £33 million. Fifty-seven years after it was painted, why does it still resonate so powerfully?

It was certainly controversial for its time for its frank depiction of an openly queer couple in pre-Stonewall America. Where the “shock” came then was in its normalizing of their domestic relationship, and that, given the gargantuan size of the painting, it was such a vibrant billboard for queer visibility. Now, some six decades later, its triumphant representation of a same-sex, loving relationship remains a powerful message that love is love. They’re just a normal couple at home. It’s truly such a sedate scene, yet still such a revolutionary one.

You’ve just released Don Bachardy: An Artist’s Life, an extraordinary oral biography that captures not just one artist’s story, but a whole queer generation. What first drew you to Don’s life and legacy?

I was in the midst of work on an oral biography of the artist Bernard Perlin when he encouraged me to “look up” Don Bachardy on a trip I was taking to Los Angeles. By that point, I’d already been deeply immersed for years in passionate research about the illustrious midcentury queer social and artistic circle that had surrounded the legendary photographer George Platt Lynes. Bernard was an intimate member of that great New York gay “cabal,” as he called it, and cast himself as its last living member. But truth be told, he wasn’t the last, exactly, for Don Bachardy had been introduced into that extraordinary circle through Christopher Isherwood in the early 1950s. So I was very excited to have what I thought would be a one-time, hopefully informative meeting with Don, whose backstory I thought I already knew well. What I didn’t expect was that our mutual discovery of each other as fervent fans of the Golden Age of Hollywood would lead to such a fast friendship between us. As our glorious conversations about art and movies and queer history and Don’s extraordinary life continued beyond that initial meeting, this new oral biography began to organically grow.

Don Bachardy and Christopher Isherwood lived openly and defiantly as a couple when few dared to. What do you think their relationship taught the world — and what does it still teach us now?

Through their very public relationship as well as their creative work, their example laid tremendous groundwork for normalizing same-sex love and relationships in American and British society. Their brave example also continues to teach us about remaining steadfast in proudly and publicly embracing our identities, no matter the contrary feedback from the world around us. As Don says in the book, “The freedom of queers to be who they are and live their lives the way they want to meant a great deal” to both Christopher and himself. “I think we shocked far more people than we realized, but … the important thing was that we carried ourselves without shame. We weren’t ashamed. He taught me: be what you are, and make it something to be glad about. And we both did feel that, so we couldn’t lose: no experience could shake us, because we knew we were right.”

Oral biography is such a distinct form — a chorus of voices rather than a single narrative. Why did you choose that structure for Don’s story, and how did it shape the emotional rhythm of the book?

Don is such a spellbinding storyteller that there was really no question in my mind about letting him tell his own incredible life story in his own eloquent, unfiltered way. The oral biography approach also felt truer to the way in which Don works as a portrait artist. Rather than taking photographs of his subjects and then crafting his portraits on his own, he paints each sitter in one intensive one-on-one session, fueled by the spontaneity and immediacy and energy of the “live” moment shared between them. So rather than just using our interviews as raw materials from which to construct a more traditional biography, I wanted to preserve a similar sense of spontaneity and immediacy, of creating an intimate portrait of Don from life, and to invite readers into the very room in which it all was recorded. The conceit of the book is that it all unfolds like one long, continuous conversation. In reality, our sessions toward this project were winding and wide-ranging, and after nearly a decade I had a few hundred hours to transcribe, edit, and sculpt into the readymade outline of Don’s life story. It was important to shape it all into an easily accessible, engaging narrative flow for readers, and to provide helpful contextual material wherever needed.

The list of people contributing to this project — from Liza Minnelli and Tom Ford to James Ivory and Sir Ian McKellen — reads like a who’s who of queer and cultural icons. How did it feel gathering that chorus of admiration around Don’s legacy?

It has been absolutely humbling and so very encouraging to have such incredible support behind this project. I’m so very grateful to them all. Their contributions are such a testament to the tremendous cultural legacies and impact of both Don Bachardy and Christopher Isherwood, both as creators and as pioneering queer advocates.

Don and Christopher were both artists in their own right, but also muses to one another. How do you see that creative and romantic symbiosis reflected in Hockney’s portrait — and in your book?

Their flanking chairs position them as equals in Hockney’s dual portrait, but how each of them is posed also suggests their intertwined identities as creative and domestic partners. Author Isherwood is looking at Bachardy, perhaps listening, certainly observing, seeming to defer to artist Bachardy, who is looking straight ahead at us, the viewers of the painting. It essentially captures the couple in typical social and creative concert with each other: as Don says in the book, they were “such a good balance together” because his talent as an artist has always been based on a passionate interest in looking at people, while Christopher’s, as a writer, was in listening, recording in his own way.

My interviews with Don took place in that same room, with Don often sitting in his same chair beside Christopher’s now-empty one. But Christopher was nevertheless present throughout our conversations, given the tremendous touchstone that he remains for Don. Don speaks of still feeling that he’s intimately connected with Christopher, certainly in reflection but also in the guidance and inspiration he continues to draw from him. So in a way, their collaboration continues, as does their love story.

You’re also the curator of Bernard Perlin’s estate, and he too moved in the same queer artistic circles. How do you see these interwoven legacies — Perlin, Isherwood, Bachardy, Hockney — shaping the broader queer art narrative of the 20th century?

Each of these extraordinary elders used his art and his public life to challenge societal norms and to advocate for queer visibility. They not only documented queer life, queer relationships, and queer expression, but courageously lived and loved openly as gay men. In essence, they shoved open the door of the closet into which society had long pushed the queer community, giving inspiration and permission for those artists and writers who have followed them. It’s an inheritance that I’ve certainly benefited from as a writer and oral historian, and so it’s become my passionate work to play a small part in preserving their incredible legacies.

The Gay Liberation era was transformative, but also deeply personal for Don and Christopher. How did their activism — subtle and overt — ripple through their art and relationships?

The gay liberation movement certainly galvanized Isherwood to become more publicly outspoken than he’d previously been. His memoir Christopher and His Kind, for which Don gave him the title, was a bold public statement of his queerness, and a corrective to his earlier, more coded writing. He became a mentor for the movement, embracing every opportunity he could to speak to various queer organizations, while Don’s own advocacy continued through his work as an artist. Throughout his long career, Don has sought to indiscriminately portray—and thereby celebrate—the vast variety of humanity, drawing and painting people of diverse racial, gender, sexual, and generational identities. This work has included numerous LGBTQ+ activists, cultural figures, and allies. But again, as one of America’s first openly queer celebrity couples—and arguably the “First Couple” of the gay community, as Armistead Maupin has called them—Bachardy and Isherwood led even just by their very public example.

Don Bachardy: An Artist’s Life captures not just fame and artistry, but also tenderness, aging, and devotion. What was the most moving discovery you made while working on the book?

Don readily attributes his having become an artist to the early support he received from Isherwood, who had encouraged him to embrace and pursue his talent. Christopher was also Don’s very first portrait subject from life, and across thirty years became his most frequent subject. Given all they shared together both as life and creative partners, it seems only fitting then that Chris would ultimately encourage Don to document the process of his dying. It’s “what an artist would do,” they decided, and it entwined them even more intimately in their final months together. In some ways, doing so helped Don process through his grief, but publicly, those final raw portraits of Chris are among the most powerful, poignant, and beautiful in all of Don’s body of work.

Finally, if Christopher were alive to see this moment — Hockney’s painting celebrated and queer love revered instead of whispered about — what do you think he’d say?

In the many years now since Christopher’s passing, Don has witnessed a huge leap forward in societal acceptance, legal rights, and mainstream cultural visibility for the queer community. Because they’d been in the vanguard of the fight for it all, when I asked Don what he thought—and Christopher might—of where we’re at now, he replied that he thinks it’s “a pretty good show on the whole.” Christopher, he said, “knew that we were going to survive it and be stronger than ever.”