Colombia’s political and spiritual heritage inspires a magnetic, transgressive work – so vivid you can almost taste it.

Andrea Peña & Artists’ make their UK debut with BOGOTÁ, which brings together ancient mythology, magical realism and baroque architecture. In this brutalist alternative world the queer body meets Colombian political heritage, both glittering and grotesque.

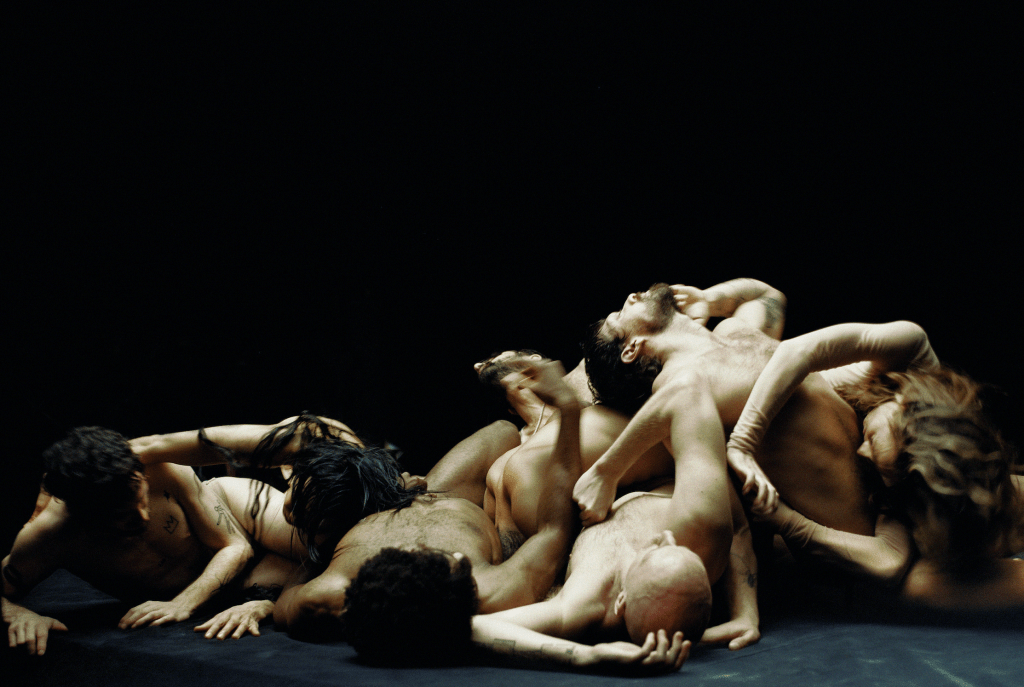

BOGOTÁ is steeped in artistic director Andrea Peña’s Colombian heritage. Cycling between chaos and rebirth, nine intense performers invite us to contemplate death and resurrection, in the landscape of Bogotá City (aka The Lady of the Shining Mountain). In this magical realist universe, movement becomes a vehicle for storytelling, uncovering passageways to transcendence and honouring the resistance of deviant bodies.

Andrea Peña & Artists is a multidisciplinary dance company, based in Montreal and noted for large-scale work that engages with both ambitious choreography and design. They create alternative universes, political and philosophical imaginings that invite the audience to experience risk-taking work of real ambition.

What inspired you to centre BOGOTÁ on your Colombian heritage and the mythology of Colombia?

For the past ten years, my sister and I have been deeply exploring our Indigenous ancestry. When it came to creating a new work, I found myself drawn to the notions of death and rebirth, ideas that are central to our Indigenous people and the ways we understand death.

My grandfather is Muisca, from the Andean region of Colombia. On a personal level, I’ve been in a process of reconnecting and gathering knowledge around our indigeneity, while also asking questions about death and rebirth, both from an Indigenous perspective and from a broader human, global perspective.

I became curious about using BOGOTÁ as a lens to speak about these themes. Colombia is a country marked by more than forty years of civil war. Death and rebirth are present not only in our colonial past but also in our contemporary history. This proximity to death shapes a particular imagination – one that allows for mythologies of celebration, joy and community. Much of our mythology is rooted in spirits, in death, and in beings that come from other worlds.

For me, this work became about intertwining those realities: What is Colombia today? What has Colombia been? And how does Indigenous mythology, woven through our everyday lives, continue to infuse meaning and presence into these questions of death and rebirth?

When did you first feel the impulse to explore the queer body in relation to political heritage?

As a queer individual and having a team that is, I would say, 90% queer, including performers, designers and producers, we’re not trying to define what queer is, as an aesthetic, but work across multiple mediums that are built by queer folk, queer communities and with a queer perspective.

A lot of what I talk about in the work – and we really use queering as a verb within AP&A – is how do we queer the body? How do we queer ideas? What does queering light look like? What does queering a space look like? I’ve been really inspired by ‘Queer Phenomenology’, by Sara Ahmed, which speaks to the experience of queer bodies in and through space. How queer bodies have forcibly built a unique understanding of space that is temporal, fleeting and constantly under construction.

For me, simply being a queer person in a place like Colombia, which is extremely Catholic and extremely religious, is already an enormous political act. The gender politics I’ve had to experience as a queer person, in my own family and my own community – it’s taken over 12 years for me to be accepted. Just being queer feels as a Latinx person feels like something very political.

These notions have been intertwining themselves in my work for a really long time. But, in particular, looking at the notion of Colombia and death and resurrection and rebirth in this piece, I was really pulled to everything that is the baroque, but looking at it from what is known as the Andean Baroque or the Latin American Baroque, which is how the Latin American people subverted the baroque that came through colonisation and how they interwove, into the architecture and the paintings, a lot of the symbolism of indigeneity or artisanal tradition.

There’s this incredible subversion in the Andean Baroque. For me, it was really important to take that subversion further and start exploring what subversion of the baroque looks like as queer. How can we queer these paintings? How can we queer these ideas? How can we queer these mythologies? I think to make a work that is called BOGOTÁ and that is extremely queer is very political, because it’s only very recently that, socially and culturally, being queer has been more accepted.

Your work is described as honouring “the resistance of deviant bodies.” How do you define “deviant bodies” in this context, and what resistance do you hope to evoke in the audience?

For me, deviant bodies are just bodies that depart from usual, accepted normal standards, both in society and in sexuality and gender. To honour the resistance is to honour, I think, the resilience that the queer body has to push against and continuously strive for in our society; to gain freedom and expression.

For me, resistance and resilience are tied together because it’s not just about resisting; it’s about being resilient through the resistance in order to carve space for the freedom to exist. While the audience witnesses a work in which bodies who experience resistance are in states of resilience, that resilience is vulnerable. I think that’s where we hope to take the audience.

The description says “death is only the beginning” and mentions cycles of chaos and rebirth. How does the choreography embody both endings and new beginnings?

I love this question. It’s a very strange thing to talk about the cycles of death and rebirth in choreography because we’re working with the living body.

One of the things we were really working on with the team is: What is the death of an idea? How do we see an idea die in the body? How do we see the decay of the body? How do we see transformation, mutation? If we’re talking about life cycles, a lot of what we’re talking about in this work is transformation. Not necessarily our Western notion of death, but more linked to a Muisca notion of death, which is looking at how the body transforms into spirit.

Choreographically trying to embody beginnings and endings allows us to see, in the body, how an idea dies. How does that idea evaporate out of the body? How does a new idea start? The dancers in this work have a lot of agency and for me it’s really important that we’re constantly seeing the agency of the performers. The artists are in constant states of negotiation that allow us to access and understand how these ideas are being born in real-time.

The company is known for “large-scale work” and “ambitious choreography and design.” Could you walk us through your creative process for BOGOTÁ?

The creative process of BOGOTÁ was really special. One of the things that it was really important for me to explore, I said to the team: “I want to make a piece from the back door,” or “I want to make a piece from the bottom up.” Traditionally, choreography and the role of a choreographer can be very hierarchical. Usually, the choreographer has the final word, and it’s a very top-down practice. As a new-generation choreographer, I asked myself, “What is the future of choreography, and what does choreography mean today in 2025?”

The way in which we started working with these artists was really open-ended. We came into the room and did multiple sessions of absolute pure research without any goal in mind. I also tried to be in this space and not decide or define what is working and what is not working. It was really nice for us, as a team, to give ourselves time to be in pure states of discovery: what does it mean to build a work from the back-door (meaning the subconscious)? What does it mean to build a work from the bottom-up and not top-down (meaning coming from the choreographer)?

That meant a lot of building skills and tools that the interpreters could carry in their pockets. For them to activate situations and systems in real-time. So, what we realized is we needed to build these tools so that the performers could navigate through situations in the scenography, which is a very big part of the work. It’s a brutalist landscape and we needed to equip the dancers to have tools to create the kind of work that I make and the ideas that I’m searching for, but that tools that they could activate in order for that choreography to be born from the energy of the ecology and not just the energy of my own brain.

What do you want audiences to feel or take away after seeing BOGOTÁ?

I think BOGOTÁ is quite a challenging piece. One of the things we talk about a lot with the interpreters is that even if we’re talking about such postcolonial ancestries in the work, and it’s woven through different ways, and we are talking about death and rebirth, it definitely is a very, very charged work. But, what we talk about with the artists is how can we activate a sense of viscerality in the audience? At the same time, coming back to the word vulnerability which really reminds me of my grandfather. How can performers give themselves the permission to be vulnerable to welcome the audience into such vulnerable places?

So I think what the audience feels is both a sense of resilience, a sort of very raw charge from all of the interpreters, mixed with a sense of vulnerability, care or softness. What I hope for an audience to take away is that it’s so subjective to their own humanity and any interpretation, metaphor or symbolism that arises for an audience member through watching a work is absolutely valid. I can’t really control the way people and their histories interweave through the way that they see what we propose but I really see these works as a meeting place between our subconscious and theirs. And it’s this philosophical collision or braiding that happens that is so beautiful.

The show is described as “risk-taking.” What were some of the most difficult risks you took in this production (movement, staging, exposing vulnerability)?

It definitely takes risks here and there. We have a ‘double gay Jesus’ in the work, for example. We laugh about that one a lot in the studio. Some could call that risky.

Bogotá is a very punk, colonial DIY, underground trash and gloriously culturally-rich city. To try to bring all of that on stage meant we use a lot of scaffolding and metal, and a lot of massive industrial and brutalist objects. You have dancers embodying, in some cases, indigenous Andean Baroque spirits while looping their bodies through scaffolding metal. A lot of athleticism is required for the loop work, against these metal objects. So, there’s also risk in terms of navigating the body through harsh and difficult materials.

We always say with the team, “If you’re going to take a risk, nail the risk.”

Are there future projects that build on the themes in BOGOTÁ—heritage, transformation, queerness, mythology—that you’re excited about?

Yes, absolutely. Queerness is always there; it’s who I am, it’s my body, it’s how I see the world, it’s how I hold space for others, and it’s how I try to lead. But BOGOTÁ is the first time that I made a work so personal to my ancestry, my people, my community, my heritage, my land, my family. Since then, questions of transformation and mythology have continuously found their way through my other works, including UAQUE, a piece we recently did with photographer Edward Bertinsky, and Transmuted Symphony, which was recently performed with TanzKassel in Germany. Those sort of themes have become anchored to my curiosity as an artist.

How do you see intersections of queerness with race, colonialism, class in your performance? Do these play a role in BOGOTÁ’s narrative or staging?

Absolutely. Those themes are at the core of the piece. Race, gender fluidity, fluidity of expression, colonialism (not just what it’s done historically, in a geographical sense, but also how the body is colonised), a sense of class. These things are very present, and sort of intertwined in a lot of the metaphors in this piece. For example, in the middle of the performance, I come down on stage – after a performer hits a piñata and while the Colombian anthem sounds through the speakers – with the Colombian flag in my hand. I get down on all fours and wipe the dancers’ sweat off the floor using the flag of my country. For me, this moment is an homage for all of the Latin American female labourers across the world. If we look at the Western and occidental world in most places, it is Latin American women that are of service, that are cleaning, that support this world. Through these moments, we hope to speak about race and the continued colonisation of bodies across the world.

https://www.sadlerswells.com/whats-on/dance-umbrella-andrea-pena-artists-bogota/

https://www.andreapena.net/apa