There are artists who work within the rules, and there are artists who remake them. George Platt Lynes was the latter—a man whose camera captured the elegance of high society by day, and the forbidden ecstasies of queer desire by night. In Sam Shahid’s sumptuous documentary Hidden Master: The Legacy of George Platt Lynes, that secret archive of sensual, unapologetic male nudes is finally given the stage it deserves.

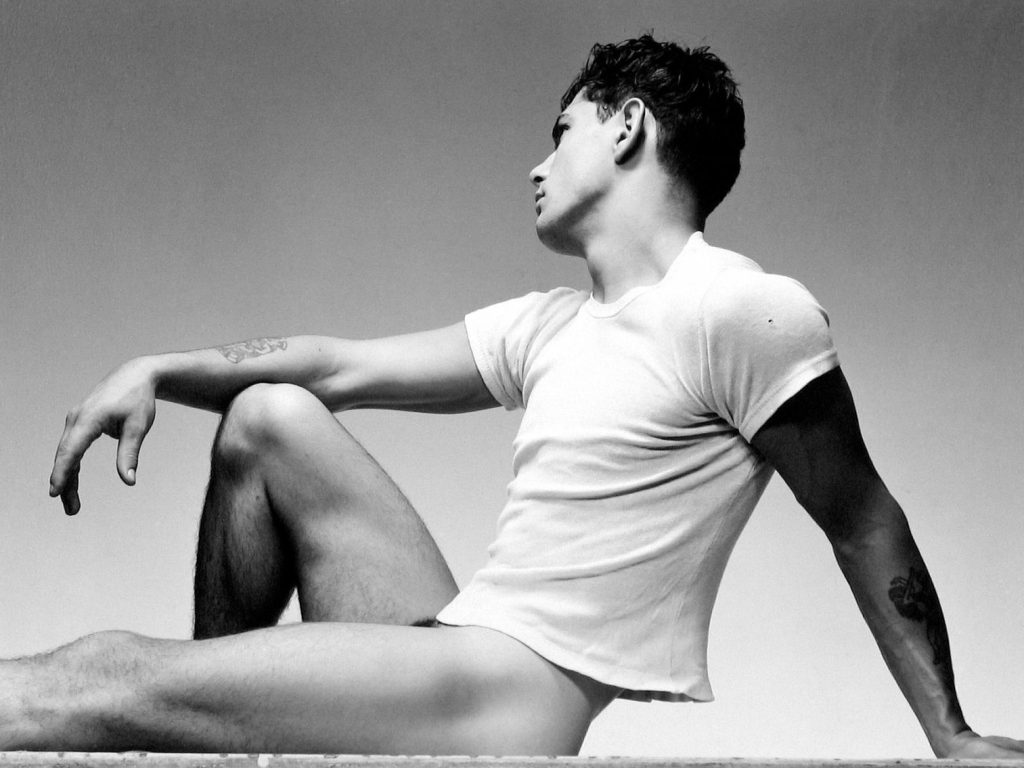

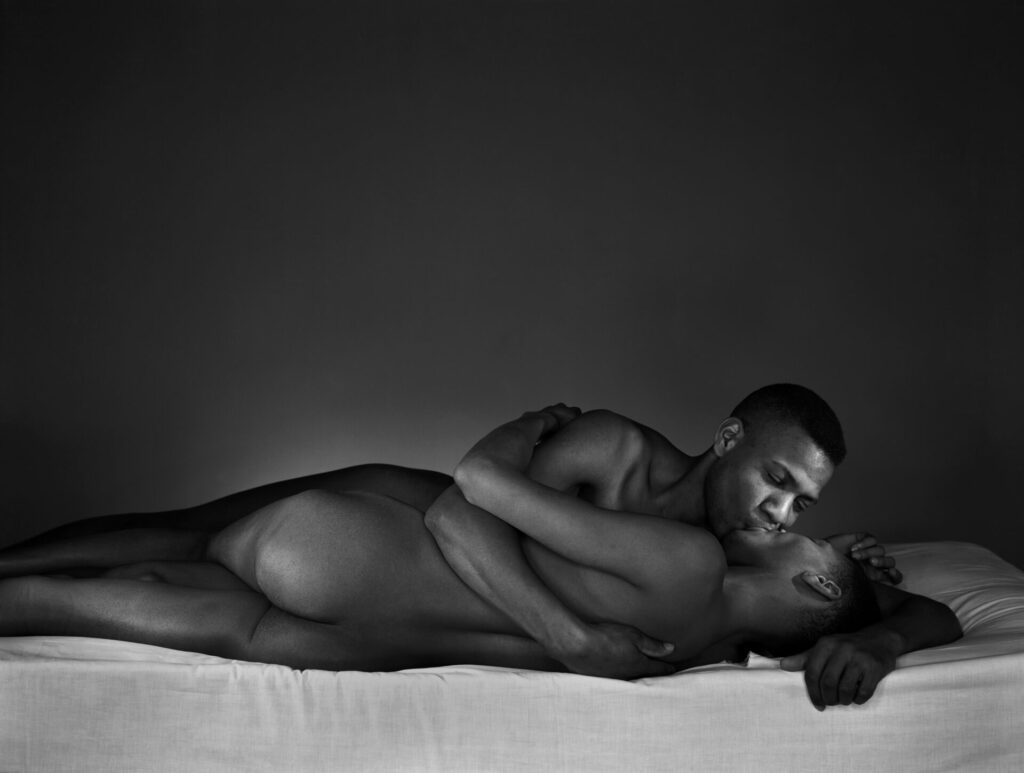

The film feels like an act of resurrection. For decades, Lynes’s most daring photographs were hidden away, too explicit, too transgressive, too queer for polite culture. And yet, when they emerge onscreen, they do so with astonishing freshness—as if these luminous bodies, sculpted by light and shadow, were waiting patiently for us to catch up. They are not merely erotic; they are reverent. Each frame positions the male body as a site of beauty, vulnerability, and power.

What makes the documentary so compelling is not only the revelation of the images but the world around them. Shahid conjures a fever-dream of 1940s and 50s New York—a queer underground vibrating with creativity and defiance. Through whispered anecdotes, lush archival material, and the voices of friends and lovers, we glimpse a hidden constellation of figures orbiting Lynes: Gertrude Stein, Christopher Isherwood, Alfred Kinsey, Bernard Perlin, Monroe Wheeler, Glenway Wescott. The film invites us into their salons, their affairs, their rebellions. It is history told not as cold fact, but as lived intimacy.

Lynes himself is revealed in duality: the society photographer adored by Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, and the private visionary capturing his lovers in moments of unabashed sensuality. The tension between these two lives—one respectable, one radical—charges the film with poignancy. Here was a man who danced at the edges of visibility, who understood both the seductions of glamour and the necessity of secrecy.

Shahid’s direction leans into lushness. The film luxuriates in Lynes’s work, letting us linger on the contours of bodies, the theatrical use of light, the surrealist echoes of Man Ray. At times the reverence borders on worship, but perhaps worship is what Lynes’s archive demands. To see these images now is to recognize not just their artistry, but their bravery.

And yet Hidden Master is more than biography—it is an invocation. It asks us to consider what it meant, in an era of censorship and danger, to create art that dared to eroticize queer love. It asks us to see in Lynes’s men not just models, but ancestors. Their bodies, captured in silver gelatin, remind us that desire itself is a form of resistance.

At ninety-six minutes, the film doesn’t overstay its welcome; instead, it feels like a door opening. When it closes, we are left with an ache—for the vanished parties, the whispered kisses, the boldness of creating beauty in hiding. But also with gratitude—that these images, once buried, are now alive again, shimmering in the light.

Hidden Master is not just a documentary. It is a love letter to queer history, a hymn to forbidden desire, and a reminder of the power of visibility. To watch it is to witness shadows dissolving into brilliance—and to feel, perhaps, a little more luminous ourselves.

Hidden Master will be available to rent and buy on digital platforms from 1 September.