An intimate conversation with Alana S. Portero on her last novel “Bad Habit”, on queer memory, literature without borders, and why community still needs physical space

Interview by Spyros Katopodis

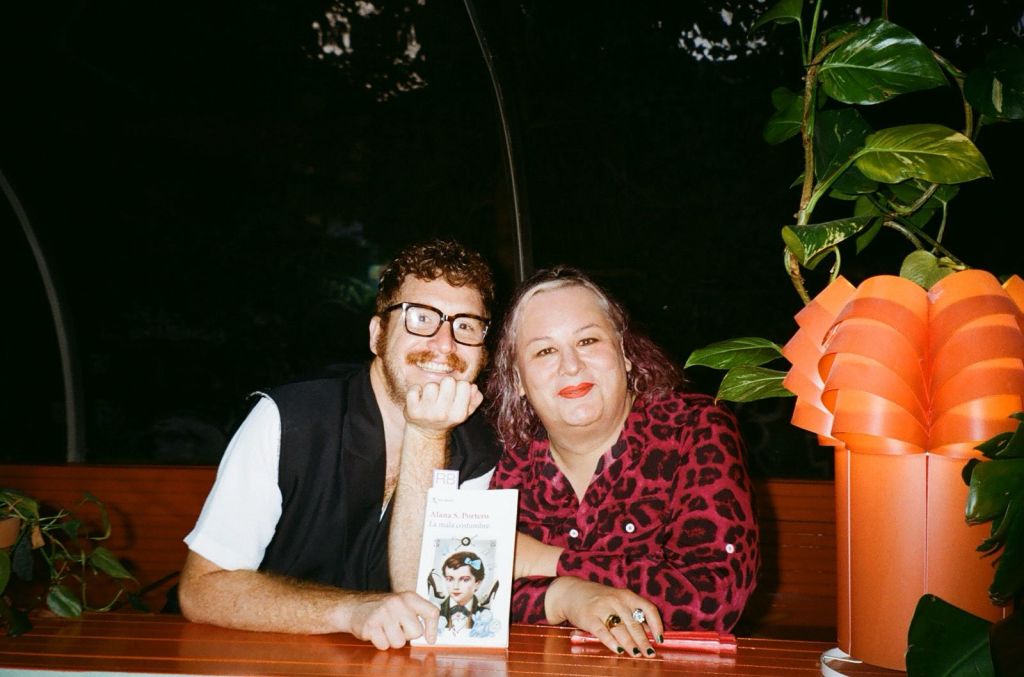

Romancero Books celebrated its fifth anniversary with Alana S. Portero who is launching her best-seller BAD HABIT in London. With her debut novel translated into over a dozen languages and embraced by readers across the globe, Alana S. Portero has become one of the most compelling literary voices of her generation. Her writing is grounded in the specificity of 1990s Madrid—its working-class neighborhoods, its emerging queer spaces—but her story has found echoes everywhere, from Greece to Iran. We sat down with her in London, where she is celebrating the UK release of her book, to talk about queer community, literature beyond labels, and the spaces we still need to find each other.

How does it feel to be in London, celebrating the success of your book?

I’m honestly thrilled. I’ve been fortunate enough to travel to many places around the world, but I had a particular debt to London—both personally and professionally. My editor is British, and I felt I owed this city a visit. Strangely enough, I’d never really known London before; it’s a city that had somehow always eluded me. So to be here now, presenting my book, feels surreal. And it’s so hot! I think I brought the Spanish heat with me.

Your book is deeply rooted in a specific time and place: that recognizable, transformative Madrid. Now that it’s been translated into several languages and read across different cultures, were you surprised by how much it has resonated with people who never knew that Madrid?

That’s honestly been the most beautiful and magical part of the past two years since the book came out. Everywhere I go, I find a version of San Blas, the working-class neighborhood that features in the novel. I’ve realized that working-class neighborhoods, and especially queer spaces within cities, share a kind of universal DNA. There’s something deeply familiar in the way people live, grow up, become themselves, and come of age in these places. Whether I’m in Colombia, Germany, Greece, or the UK, readers recognize something of their own lives in my story. That’s extraordinary to me. It’s also made me reflect on how alike we are—across borders, across languages.

The more I travel and share my book, the harder it becomes for me to understand the divisions of geopolitics. I mean, I have readers in Iran, Argentina, and Germany who all tell me they see themselves in my characters. Of course, cultural specificities matter, but our core experiences—especially as queer people—are strikingly similar.

Your novel deals with many themes, including the latent and explicit violence the queer community faces. Do you think we’re at risk of returning to darker times—or perhaps we never fully left them?

I think our victories are very fragile. That’s the real issue—we never entirely left those times behind. In fact, I believe we’re in a period of regression. It’s heartbreaking to say this, but I’m currently in a country—here in the UK—that has introduced legislation explicitly targeting people like me. And this isn’t some far-flung place; it’s part of the so-called Western cultural core.

Even more troubling is that some of this regressive policy is being pushed by sectors of the political left, which is deeply alarming. It should be a wake-up call. Queer people—we do what we can. But really, it’s the cis-heteronormative world that needs to wake up and take responsibility. We’re exhausted.

One of the most moving aspects of your book is the importance of queer spaces like Chueca, where the protagonist begins to connect with the community. Do you think the story would have been different if written today, in the age of the internet and social media?

Absolutely. The past wasn’t necessarily better, but it was different. One thing I miss from my youth is the clarity: we knew where to go to find our people. There were physical places—bars, neighborhoods—where you could simply show up and be among others like you. That kind of tactile community matters.

Now, digital platforms make it easier to find people, but harder to build deep, lasting connections. I think the idea of “community” gets diluted online. That said, I’m a terrible user of social media—maybe younger generations are finding ways to make it work. But from where I stand, I feel a bit nostalgic for a time when I knew exactly where to go and who “my people” were—not as avatars, but in person, in the flesh.

If your book were adapted into a screen project, would you prefer it to be a movie or a series?

A film, for sure! I’m a die-hard cinema lover. I enjoy series, absolutely, but there’s something about the emotional compression and impact of a film that feels right for this story. If I could choose, I’d go for a movie.

And who would you cast as the lead characters?

That’s such a tough one! Honestly, I have a much clearer vision of the secondary characters than I do for the main ones. The narrator—the child, the teenager, the adult version of her—that’s a complex casting decision. But there’s a character named Antonio, the bar owner, who I always picture as played by the Spanish actor Luis Tosar. He just is Antonio in my mind. That said, actors always surprise you—sometimes the perfect person for a role is the one you least expected.

In another interview, you mentioned being tired of your work always being labeled as “LGBTQ+ literature.” Do you still feel that way?

I do—and not just for my own work, but for all LGBTQ+ authors. That label is essential when we claim it, when it comes from inside the community. But when it’s imposed from outside, it becomes a way to shrink our work, to box it in and make it only for us—as if our stories couldn’t speak to the whole world.

And that’s simply not true. Our literature is universal. As Camila Sosa Villada—author of Las Malas—so beautifully said, we have the right to be universal. I follow in her footsteps, demanding that right. I won’t allow anyone to make my work feel small. It isn’t. None of our work is. The literature of our community is not niche—it’s for everyone.

“Bad Habits” by Alana Portero is now available in English by HarperCollins Publishers. Follow her work and appearances here: https://www.instagram.com/transisteria/?hl=en

A big thank you to Cervantes Institute London, The Spanish Embassy in London and Romancero books for making this interview possible.