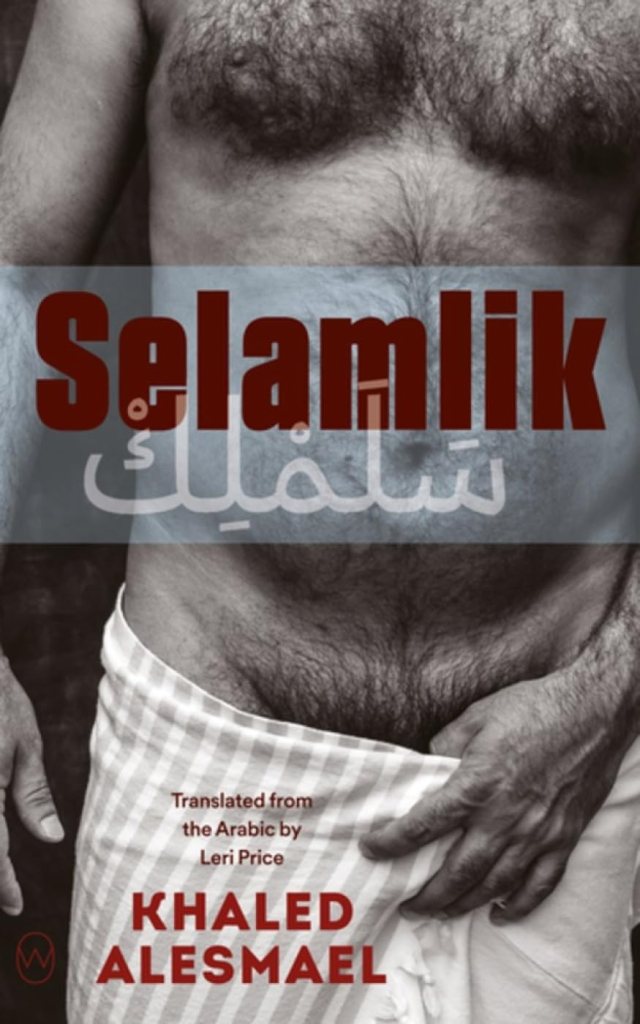

Escalating global crises are driving intolerance, displacement and economic instability and never more so than amongst the LGBTQI+ communities in the war-torn hotspots of the Arab world. Selamlik is the story of Furat, an 18-year-old queer man who falls in love with his roommate, Ali, in their student dormitory in Aleppo. Uncertain how to navigate their feelings in a country teetering on the edge, Furat and Ali take refuge in their room, discovering a forbidden love in a country that criminalises homosexuality. But when the civil war erupts, his world is shattered. Adult life is suddenly thrust upon him.

Fearing for his life, Furat—like the Euphrates River he’s named after—embarks on a long journey far from home. He escapes through Turkey and reaches Europe, where refugees confront hostility in more ways than one. For Furat, his identity as a queer refugee makes him a target on multiple fronts. Nowhere feels truly safe, not even the remote asylum centre in the Swedish countryside, where he ultimately arrives and begins to tell his unforgettable story.

As we follow Furat’s quest for love and acceptance, we witness the trauma endured by the queer community and the harsh challenges refugees face in their search for a new home in Europe. The novel’s fragmentary structure and flashbacks intensify this sense of displacement, immersing readers in Furat’s fractured reality.

But Selamlik is more than a story of war. Darkly humorous reflections on humanity and unexpected moments of levity—against all odds—paired with Alesmael’s exquisite prose make this a deeply cathartic read that resonates universally. Selamlik is a powerful exploration of identity and belonging and marks the emergence of a vital new voice on the international literary stage.

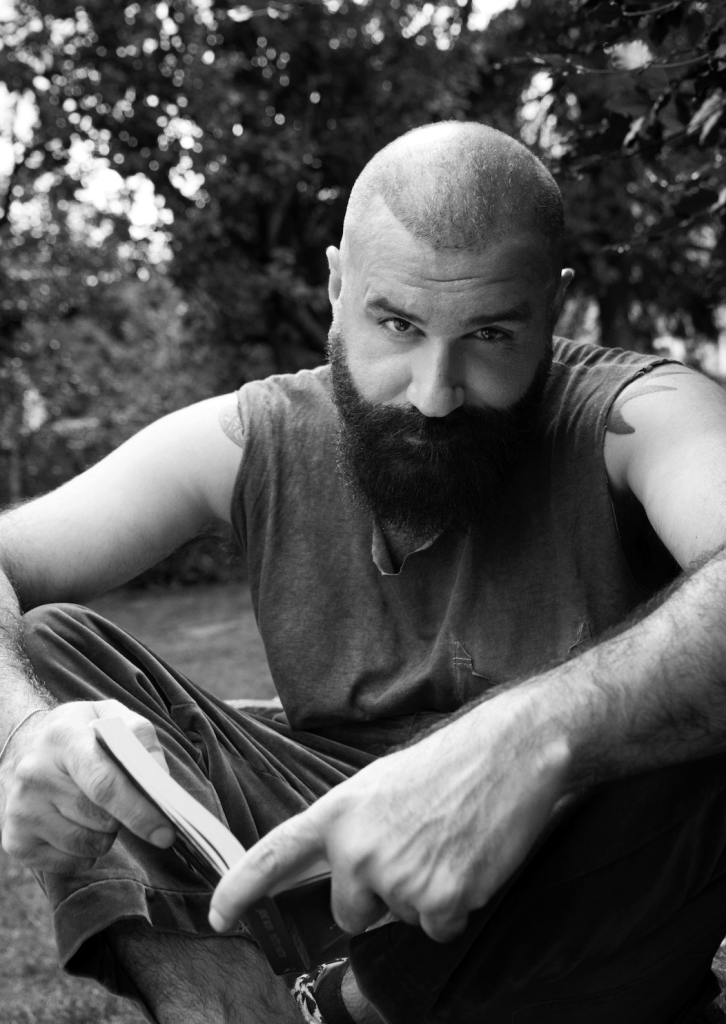

Khaled Alesmael is an award-winning Syrian-Swedish queer writer, journalist, and public speaker who lives and works in in London. A graduate of English literature at Damascus University, he has published several works, including the novel Selamlik, which was recently translated into English for the first time by World Editions. His second book, Gateway to the Sea (published in Swedish and German), takes the form of ten short stories exploring the personal narratives of gay men from Syria, Palestine, Israel, Iraq, Yemen, Western Sahara, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Lebanon. His writings on the queer community and migration—in both English and translated to foreign languages—have a dedicated international readership. He is a founder of the Arabic Creative Writing Course at Gothenburg University and his speaker credits include the University of Oxford.

We invited Khaled to YASS Magazine and this is everything we talked about.

How easy or difficult was it to tell your personal story through your book?

Writing Selamlik was both liberating and challenging. While it’s not my story, it is a story deeply informed by my lived experiences, by the lives of people I have met, and by the weight of memory and exile. Fiction gave me the freedom to explore difficult truths without the constraints of autobiography. The challenge was in capturing the emotions honestly while allowing the story to belong to Furat, my protagonist, rather than to me.

How did you feel sharing your experiences and struggles as a queer Arab immigrant?

Again, while Selamlik is not strictly my personal story, it is the story of many queer displaced Middle Eastern individuals—stories I have witnessed, heard, and, at times, carried within me. Writing it was an act of giving voice to those who often remain unheard. I felt a deep responsibility to tell it with authenticity, respect, and care, ensuring that the emotional truth remained intact, even if the events were fictionalized. I wanted to create hero for myself at first.

How did these experiences shape you?

Living in exile, being queer, and navigating multiple identities have shaped me into someone who constantly negotiates belonging. These experiences have made me more aware of the power of storytelling—how it can preserve what was lost, reclaim what was denied, and offer visibility where there was once erasure. Writing Selamlik allowed me to explore these themes with both vulnerability and defiance. Selamlik is my coming out to myself and to the public as my Arabic community knew me as a journalist and podcaster only before.

How did the British audience react to your book?

I am overwhelmed by the response. Many British readers, whether queer or not, found Furat’s journey deeply moving and eye-opening. Some were shocked by the realities faced by queer Arabs, while others saw parallels with their own struggles for identity and acceptance. Selamlik resonated with a wide range of readers, and that, to me, is a sign that literature can transcend borders and backgrounds. Many readers compare the life of Furat back in Syria to the life of gay men here in the UK back in 70s. A reader sent me the anthology of Peter Parker as a present as he found the life in Damascus that I spoke about in Selamlik similar to London in Parker’s books. Fact that the bookshop Gay’s The World includes my book Selamlik and Parker’s Some Men in London in the best books of 2024.

Your book follows the compelling journey of Furat, a young queer man in his early 20s, as he’s forced to flee his home in war-torn Damascus and make the long, perilous journey to Europe. Are you this young man?

Furat is not me, but there are parts of me in him—just as there are parts of many queer Arab men in him. His fears, desires, and survival instincts are shaped by real experiences. I wrote him with the hope that readers, both Arab and non-Arab, would see him not just as a refugee, not just as a queer man, but as a full, complex human being.

What are the similarities and differences you have with the main role of your book?

We both love bearded men 🙂

Joking, in fact like Furat, I have navigated exile, longing, and the tension between home and elsewhere. The difference is that my journey, both physically and emotionally, took a different route. Furat’s story is more extreme in some ways, but emotionally, I relate to his search for belonging, love, and the right to exist on his own terms. Fuart is my idol in many ways.

What does it mean to be one of the few contemporary Arabic authors to write openly about their LGBTQ+ experience?

I’ve never really thought of it that way—I always focus on how we can increase the number of writers. There are many queer Arab writers, but not all of them have the platform or the safety to be open. Homosexuality remains criminalized in all Arab countries except Jordan, which creates significant barriers.

I am the founder and teacher at The Online Creative Writing Course in Arabic for migrants at Gothenburg University in Sweden while living in London. Three queer writers participated, yet they were still negotiating whether to be open about their gender identities. They feared not only the repercussions from their home countries but also the lack of support in the racist as well as discriminatory environments of their host communities in exile.

How has your life changed over the last few years?

Life has been a series of transitions—both in geography and identity. I have grown more confident in my voice, more assured of my place in the world, even as I continue to navigate uncertainty. My writing career has evolved, and with it, my understanding of who I am and what I want to express.

For my second book—which has not yet been published in English—I had to conduct extensive research, interviewing more than 30 LGBTQIA+ individuals from Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Morocco, Yemen, and Saudi Arabia, as well as those living in exile. The result is Gateway to the Sea, a collection of ten fictional stories about queer Arab individuals.

This book taught me the importance of kindness before gender. My characters, above all, seek kindness in their lives. I also learned that resistance takes many forms—one of them is simply allowing yourself to experience joy and happiness.

How is life in London now?

London is a paradox—it gives me freedom and anonymity, but it also reminds me of displacement. It is a city where I can be openly queer and creative, yet I often carry the weight of the places I left behind. It is a space of reinvention, but also of longing. There is a New Syria not Free Syria as we demanded in 2011. New Syria is a vague and not a triumph for me until the new institution will be issued without article 520 that criminalise homosexuality. The fight of the queer individuals will not end there but it will shift to be a confrontation with the society, but it will be possible if the law will protect the queer individuals. London is so inspiring, and my coming book is about it.

What is the best comment you have received?

From Arabs: You wrote about me in Selamlik

From Westerns: Your writing reminds me of Jean Genet’s and Patti Smith’s style.

http://www.khaledalesmael.com | Instagram: @khaled_alesmael | X: @KhaledAlesmael